Dodging the dog and making a pass at the scullery maid

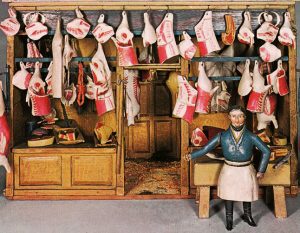

‘My father was a butcher.’ He looked at the makeshift coffin, his face expressionless. ‘Mustn’t develop delusions of grandeur. A butcher’s assistant. Though he was given a shop to manage in the end. He died the year after.’

‘How old were you then?’

‘Fourteen. And there was a slump on at the time. I got permission to leave the grammar school, and get a job as a clerk. Twelve and six a week. I could have got another half crown as a butcher’s lad, but my mother wouldn’t have that.’

‘You had a rough time of it.’

George shrugged. ‘So-so. The war made the difference, of course. I was lucky enough to get into air crew, and qualify as a pilot. That was the difficult bit; the rest was a piece of cake.’ He grinned. ‘To use one of the many habits of speech I picked up in the process.’

‘First-class assimilation,’ Selby agreed. ‘Has it made you happy, do you think?’

With good-humoured scorn, George said: ‘There speaks the man for whom a butcher’s assistant was something in a blue and white apron at the back door, dodging the dog and making a pass at the scullery maid. My life may not look much of a success by your standards, chum, but it is by mine. Reasonable comfort instead of grinding poverty. And when I look out of my front window I see Grammont and Lake Geneva, not the other side of Crake Terrace with cur dogs peeing up against the gate-posts. I bring my mother out every spring. She’s as mad on these bloody mountains as I am.’

Selby nodded. ‘I take the point.’

‘Do you? Maybe.’ He moved closer to the table, and looked down at the child’s body. ‘The changes and chances are out as far as he’s concerned, aren’t they? Poor little sod. What a waste.’

There were footsteps outside, and Ruth Deeping came in, her husband shepherding her. George moved away as she went to the table and stood there. Her face was white and still. George nodded slightly to Selby, and they went out together.