An abominable dancer

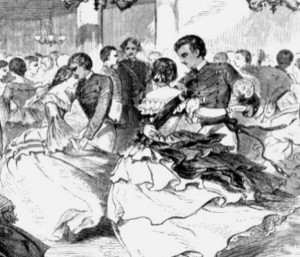

‘An abominable dancer, as I say,’ d’Aurigny said. ‘I lay no claim to excellence myself, but I promise you I am doing you a favour by exchanging for him.’

She stared at him, feeling her face go white.

‘You do me no favours of any kind, sir. There is only one you can do, which is to grant me freedom from your company. I beg that you will do so without delay.’

‘You have spirit as well as beauty, Miss Lorimer,’ he said admiringly. ‘But I assure you that quite apart from his dancing Ogier is a detestable fellow. It astonishes me that he should have presumed to engage you – even that he should have demeaned this assembly with his presence.’

She remembered what Edmund had said about the attitude such families as the d’Aurignys had to the rest of island society. The present incident clearly reflected it. She was not sure whether she was angrier with d’Aurigny for his insolence or with the wretched Ogier for submitting to it. Turning away, she said:

‘If I am not to be permitted to dance with a partner of my choice, I am most certainly not to be forced into accepting one whose conduct I find discourteous and hateful. Goodbye, sir.’

‘I will not accept that dismissal. If I have offended you, Miss Lorimer, I humbly beg pardon. It was no part of my intention.’

She remained silent, her head averted. D’Aurigny went on: ‘You are with the Jelains, I believe? Shall I plead with Mrs Jelain to soften your obduracy?’

His tone was not sneering, but her resentment provided the sneer. To a d’Aurigny the Jelains were to be classed with the Ogiers, as people whose presence depended on the whims of their superiors. Mrs Jelain was presumed to be flattered by the thought that such as he would deign to notice her visiting cousin. She said in a low, intense voice:

‘Go away.’

The fiddles struck up. He put out his hand towards her; to take hers, she thought, and pull her by force into the dance. The notion of such a contact, of the arrogance from which it stemmed, was unbearable. Turning back to him she saw the beginnings of a smile on his face, before her hand came up and slapped him ringingly on the cheek.

The sound seemed to echo through the room. The fiddles faltered, then continued, but eyes turned from all round in their direction. D’Aurigny stood stock still. His hand was extended, holding the card; and she realized she had been mistaken over his intention. He had not been trying to draw her into the dance, but returning the card.

They stared at each other while others stared at them. His face, too, was white. He said, in a low voice but clearly: ‘I beg pardon, Miss Lorimer.’

Then he turned and made through the press of people towards the door.