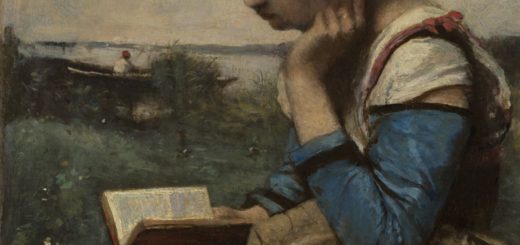

Not a true lady

It was Sarnia’s habit to cross the road by the entrance to Chancery Lane, where the sweeper was Gimpy Jimmy. He was a tall thin white-haired man who had left a leg in Spain, fighting under the Duke’s command. He would never accept a coin from her, and she had ceased to urge it on him. He was puzzled, she knew, by the fact that, although a lady in appearance, she went to work. He himself was not in need of money. The position was a good one, and he had lived frugally and saved over the years. She had met him once on Sunday in the park, dressed in a suit of  good sober serge, the rags of his trade put aside.

good sober serge, the rags of his trade put aside.

Before she crossed she heard the rattle of hooves on granite, the warning halloo of the driver, and paused to watch the yellow and red omnibus dash past in the direction of Liverpool Street. It came from Paddington, and brought to mind the little house there in which she had lived with her mother. The memory of bereavement still had power to shock; a cold hand on her heart. But she would not dwell on it – she had steeled herself against that.

‘A good morning to you, ma’am,’ said Jimmy, his broom musket-erect.

She smiled. ‘Good morning, Jimmy.’

‘Not but what it’s a dirty one. Though I have never known a lady to handle her dress more delicately when the road is muddy.’

She accepted the compliment with another smile, and passed on. In fact it was a familiarity – he would not have spoken of her manner of carrying a dress to a true lady – but she did not mind it. He meant it kindly. She reflected with annoyance as she stepped up from the pavement and dropped the hem of her coat that however deftly she managed the crossing, on a day such as this her petticoats were bound to be dirtied. But her coat and dress at least were unstained.