A stiff white hand

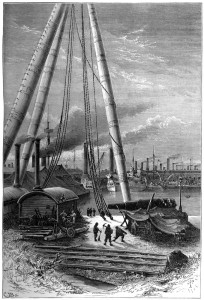

They brought him back from the dockyard on a cart. It was a cold day, with drizzling rain, and the men who accompanied the body were wet and bedraggled. They had covered him with a tarpaulin, but one hand was exposed and rain had made a small puddle in the upturned palm. I did not need the halting and confused explanation from his fellow exciseman, Jos Larrimer: the hand, with the heavy gold ring on its little finger, told me everything. I put my own hand to my face, and touched the spot where, only a few days before, it had struck me.

From inside the house, Mama called: ‘What is it, Jenny?’, as Larrimer stumbled on: a fall from a ship’s side … dead instanter … no pain … no one’s fault … a sad accident.

I could smell the rum on his breath. Although it was morning, scarcely past eleven of the clock, he was well in liquor; and my father, I could be certain, would have been drunk. The excisemen, well supplied by their calling with the instruments of intoxication, started their drinking early. Drunkenness was one of the things I had loathed in him, but I blessed it now. I stared at the stiff white hand, realizing that never again would it clench into a fist.

My mother, getting no answer, came to the door. She was longer than I had been in grasping the situation. She stared at Larrimer and at the cart, at the drenched figures of the other two men, but somehow her eyes avoided the out¬stretched hand and the bulge under the tarpaulin. It was only as Larrimer launched, even less coherently, a second time into his explanation, that she took it in. Then with a scream of pain and despair she rushed out to the cart, dragged down the top edge of the tarpaulin, and flung herself on the corpse, embracing it.