The thought of self-revelation

‘I like things to be out in the open, Charles. To me, it’s the only basis for human relationships. You could have told me if you’d not wanted us to get in touch with your friends out here.’

Hibson was uneasy for a moment. ‘What reason would I be likely to have for that?’

‘Well, social. You might have felt we weren’t the kind of people your Swiss friends would want to know.’ He glanced at Hibson quickly. ‘I’m being frank with you, Charles. I think it’s best.’

‘What kind of people did you think we knew out here?’ Hibson asked. ‘We were a very ordinary family.’ He paused. ‘In any case, we haven’t any friends here now. As far as I’m concerned, it’s all past and forgotten.’

‘Then why not mention it?’

Since there had been so much of defiance in coming back, the possibility of people like Tilling finding things out, not now but at some future time, had to be admitted. If that happened, part of him would be betrayed, but it was a betrayal he had almost come to court. To attempt any deception but the simple one of reticence, and to be caught out in it at last, would be a betrayal of a different kind: the betrayal of his present adult self.

He said slowly: ‘Perhaps the reason I didn’t mention it was because the time I spent in Switzerland was not altogether happy.’

‘Wasn’t it?’

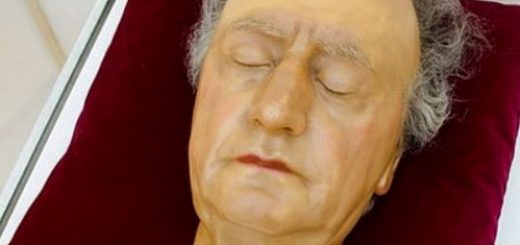

Hibson looked at him: the small figure poised against the steering-wheel, propped up on a leather cushion that matched the upholstery, ready to listen, ready to sympathise and advise. He could remember times when he had been tempted by the thought of self-revelation, of baring the wound; doubtless he would be again. But not, he was entirely confident, in the presence of such as Tilling.

‘No,’ he said, ‘it wasn’t.’

‘Anyway,’ Tilling said, with some disappointment but with relief, ‘I’m glad there was nothing deliberate about it.’

‘No,’ Hibson said, savouring the irony, ‘nothing deliberate.’