A good husband

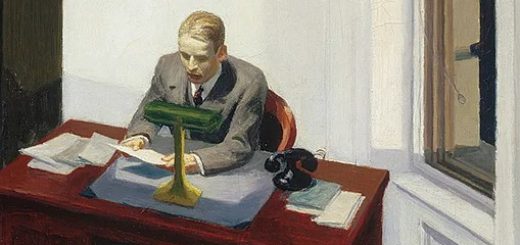

Solly sat in the rocking-chair, watching the fire, listening to its gusty, intermittent breathing and to the more distant noises of the children outside. She  handed him the cup, still without saying anything. He took it, and looked up helplessly.

handed him the cup, still without saying anything. He took it, and looked up helplessly.

‘It’s hard to say it, Mary.’

She softened. ‘Don’t, then. God in Heaven, it’s your own affair.’

‘No.’ He drank the tea almost in a gulp. ‘It’s not that I mean anything against Benno – or – you – you know that.’ She looked at him, completely puzzled. ‘Only if I married – someone like Jinny, I could not go to synagogue. It’s important for me.’ He gazed at her miserably. ‘You should not have asked me.’

It was a raw spot he had touched. She flared quickly. ‘And why not? Are you telling me Benno could not go to synagogue because he married me?’

‘No,’ he said. ‘No, Mary. I am not saying for Benno. It is just something for me. To Benno it is not important being a Jew. He may be right. But to me it is important.’ His eyes were still on her. ‘I am sorry.’

Mamma was still smarting, but Solly looked ludicrously unhappy. She began to see the funny side, also, of her attempt to convince Solly that he was not unworthy of Jinny. She smiled, and Solly smiled anxiously with her.

‘Then we shall have to find you some nice Jewess,’ she said. ‘You should be married. You would make a good husband.’

For Mamma, the only necessary qualification for a good husband was to be well-meaning.