A stranger in that fair country

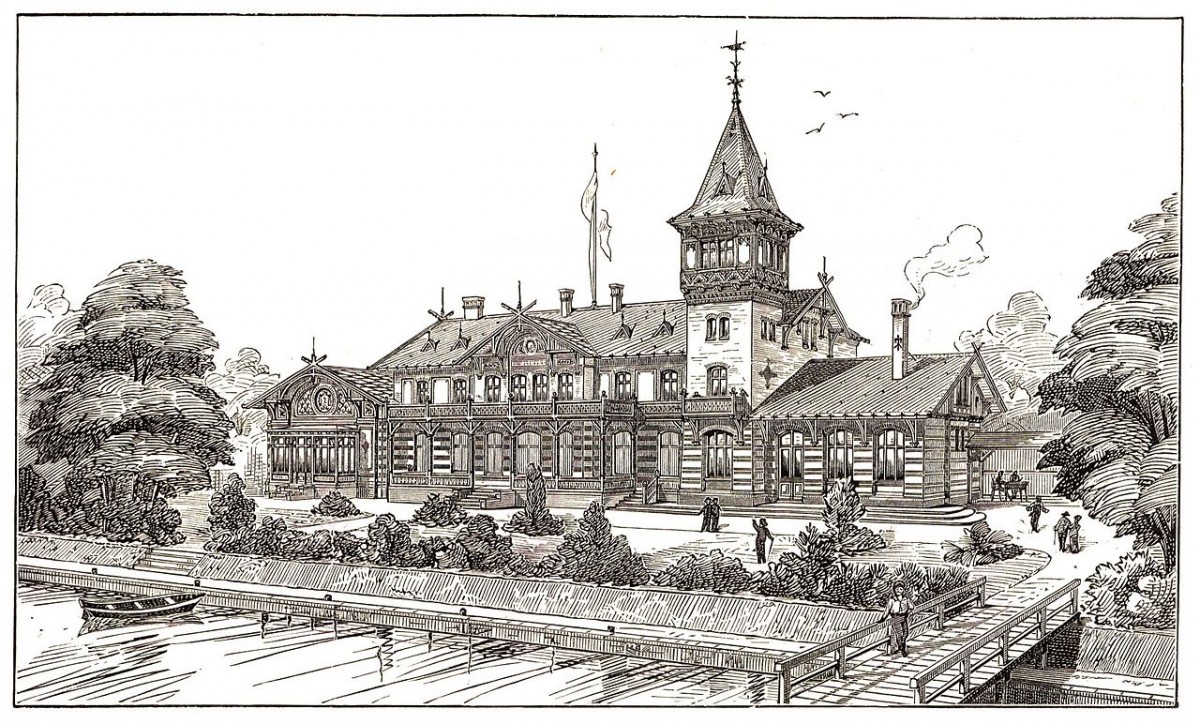

They walked across the park, and Isaak spoke of youthful excursions to the Plänterwald. It was his intention, without being too obvious, to point the contrast. Then, that broad and formal beauty under wide blue skies. Now, the patch of tired green and mud, the sky tattered streaky grey over the close unlovely ranks of houses. It was impossible that Dadda should not feel something of nostalgia, something of regret. His hopes for the future would not, perhaps, have steeled him without the awareness that he, the unfavoured son, had been a stranger in that fair country too.

The houses were larger on this side of the park, and built in pairs. The synagogue stood by itself on a corner; it was a squat, ungainly building constructed of brick that still showed faintly yellow through the inevitable Liverpool grime.

‘Why not come in with me,’ Isaak said, ‘now that you are here?’

Dadda said: ‘There are some rents that I can collect nearby.’

He fished in his pocket. ‘I have my book with me. I always have it with me. I will meet you here in an hour’s time.’

Isaak said: ‘As you wish, Benno.’ Then they separated. Dadda, from further up the street, turned to look back, but Isaak did not pause, even for a moment, in his own course.