I always have a strong inclination not to write

I glanced beyond him to where Rupert was resting his long body against the wall. He looked more melancholy than ever, although I should have known him better than to form generalizations based on his outward appearance. At any rate, I felt that Britton owed him some conversation, as a token return for his introduction to Regency Gardens and thus, at the very least, for the discovery of a stick with which to beat materialism’s aged back.

I said: ‘You’ve still not tackled your job of persuading the nightingale to start singing again, Rupert. You might as well start while you have the chance.’

Britton looked startled for a moment. Rupert said:

‘I don’t really see how you could have stopped writing poetry.’

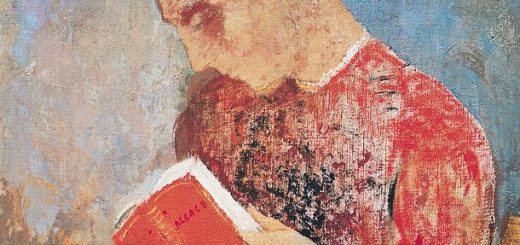

Britton smiled, gently reminiscent.

‘I was always a writer … in mood, as you might say.’

‘But that fluency!’ Rupert objected. ‘Sometimes when it reads easy it comes hard, but it came easily enough with you. That sonnet – Orchids and tulips by their dreams devising – I saw you throw it off in half an hour. And you sent it off without a word’s correction or revision.’

Britton nodded. ‘In mood. In mood it came easily, and fast. But the mood itself was hard to find, harder to pin down. I always have a strong inclination not to write. In the old days I did my best to overcome the inclination, but for years now I haven’t bothered.’

‘Haven’t bothered!’ Rupert echoed. ‘But what else is there worth bothering about?’

‘Surely,’ Britton said, ‘a whole number of things!’ He glanced at Rupert slyly. ‘Meditation, for instance?’