I’m glad, I’m glad!

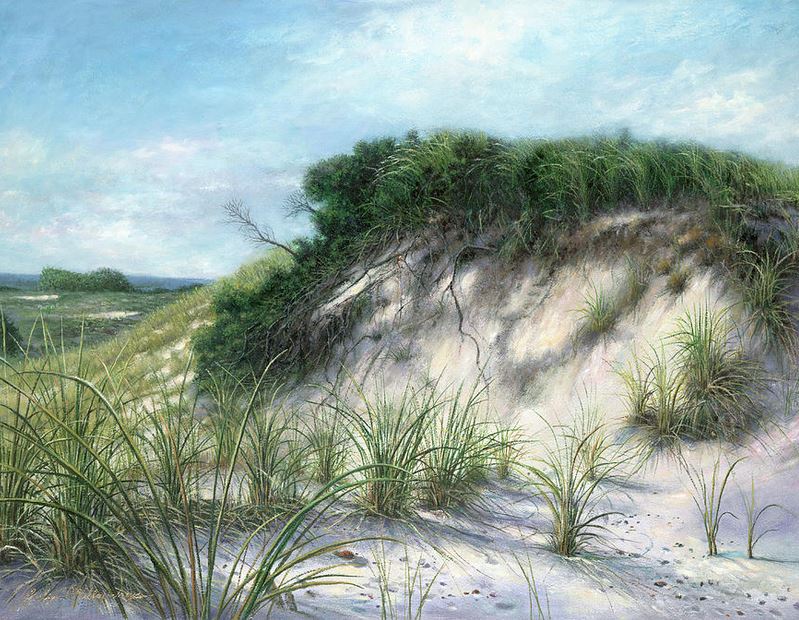

We scaled the dunes together, pulling ourselves up by the tufts of grass which had found a footing in this unpromising ground. On the top we stared out towards the distant sea, and the even more distant flecks of white that were sailboats on it.

Anna said: ‘We could reach it.’

She had said it before and each time it had seemed afterwards as though it really had only required a little extra determination to have set out across the sand and come at last to the glassy, lapping sea. But now we faced the reality again; sand stretching out in dune and hillock and plain all round us, frightening in its extent, and the sea no more than a sliver between sand and sky.

Anna said angrily: ‘By myself I would go.’ I looked at her. ‘Don’t you believe me? You stay here, then. I’ll go.’

‘No; don’t go, Anna. I know you would. But it’s too far for me. Let’s climb the next dune. We can see more from the top: it’s higher.’

She allowed herself to be persuaded. We went from dune to dune, scaling heights that were always in sight of the sea. We pretended, at last, that we were lost. I say, pretended, although I cannot be sure for Anna; she may really have lost her bearings, though I doubt it. For me, anyway, it was a game. We were hunting now for Mamma and Dadda, for Jinny and Solly and Isaak.

The dune from which we had set out had a deep curve bitten out of its side. We went up it in pretended desperation and then, coming to its crest, cried in relief at the sight of the brown picnic basket and the people lying round it. But they were not all there: Jinny and Isaak were missing.

‘Track them,’ Anna said.

We found them, easily enough, just out of sight of the others round the side of the dune. They were certainly kissing now, lying against the sandy hill with Jinny’s arms folded protectively about Isaak’s shoulders. I laughed. Anna watched them silently.

‘He’s going back next week,’ she said. ‘I’m glad, I’m glad!’