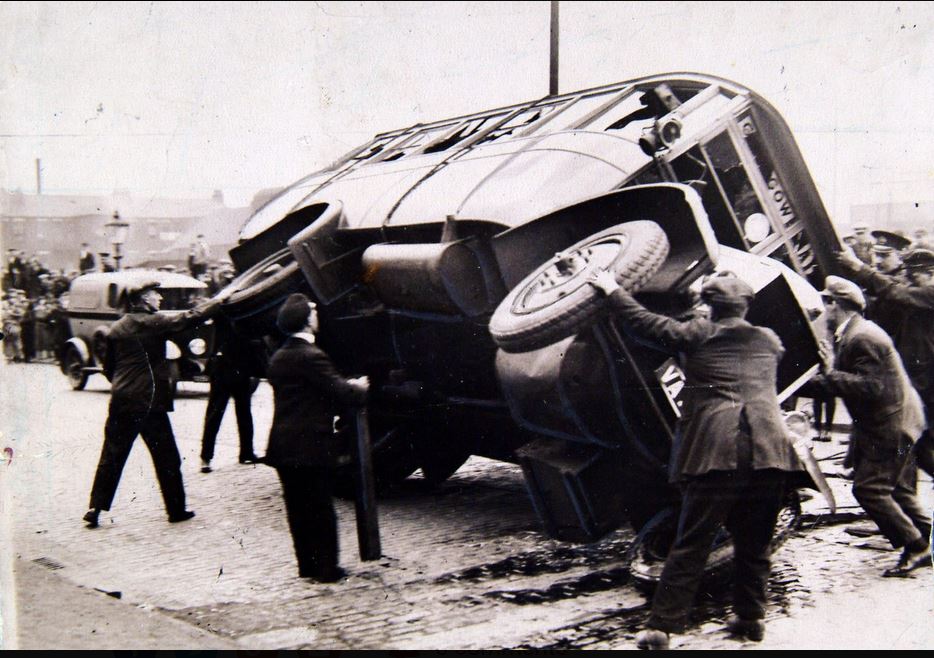

‘Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay’

The strikers were coming out of the café, talking among themselves, orderly and purposeful. They went past Stephen and Harris, and the swarthy leader climbed on to the back of the bus.

‘All change,’ he called. ‘This one ain’t goin’.’

The few passengers came out, grumblingly obedient. Stephen went round to where the men stood in a bunch.

‘What’s the idea?’ he asked. ‘The police will clear you if you try picketing.’

The swarthy striker answered him.

‘We’re not picketing,’ he said. ‘Keep yourself an’ the kid out of the way. We’re turnin’ ’er over.’

He waved his arm to the others. ‘All right, boys. All together. Give it a swing. Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay.’

Stephen could feel only a sick, nauseating anger. These were the masses, the masters by weight of numbers. It had been almost happening for a long time and now it was happening. Their offhand refusal to bother with Harris and himself made it worse. His anger and disgust and despair twisted and grew, scalding his mind out of logic and apprehension, out of everything except the certainty that they must not win, whatever the cost. They were not men, he saw now, only misshapen sub-men. They were the despised and the rejected, and they must not win. He shrieked sudden, meaningless vilifications at them. Through air that was stifling like cotton wool he heard them chanting:

‘Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay.’

The huge wheels began to lift away from the ground. He ran round to the other side of the bus and pitted his puniness against them, pushing, straining, to keep it level on its wheels.

He heard Harris’s voice calling in horror and confused shouts from the sub-men on the other side. He looked up, smiling, to see the red wall leaning over him like a petrified flame.