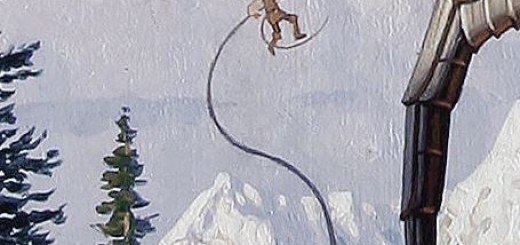

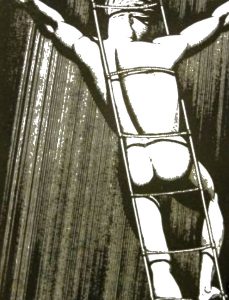

The alternation of hands and feet

It was steel and nylon and hung from the bulwark, forward of the stern on the starboard side. It reached the ground, and more – the extra lay in a tangled untidy heap on the sand. Matthew went to it and tugged, at first gently and then with all his strength. It was firmly secured at the top. He looked at Billy, and said:

‘What about it? Shall we go up? Do you think you can climb a rope ladder? It’s pretty high.’

‘I’m sure I can! Honest.’

‘You go first.’

The boy went up easily. Matthew let him get a few yards’ lead and started up himself. The ladder swung and bucked under their combined weights and he had a wave of height nausea. He halted, clinging tightly to the steel rungs, and the deep earthquake fear superimposed itself on the vertigo, petrifying him. If a big shock came, and this steel wall tilted and slid towards them … He tried to tell himself how absurd it was, but reason was overwhelmed by terror. Shaking, he heard Billy call down something. His first response was a meaningless croak. Clearing his throat, coughing, he forced himself into speech.

‘What’s that?’

‘I said I’m nearly up! But it’s harder. The ladder bangs against the side.’

‘Rest a while,’ he called.

‘No, I don’t need to.’

Gradually the fear diminished into something which, although it chilled him still, could be controlled. He moved one foot up, reached with his hand for a higher rung. He began to climb steadily, not letting himself think of anything but the mechanical process, the alternation of hands and feet.