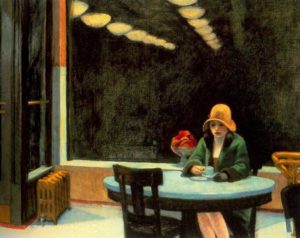

The lonely are the hard ones

I was always anxious to co-operate with Anna in avoiding subjects about which she was sensitive; sensitivity made her ferocious. But I raised the matter with Dadda in the office one day. I had come in early from my round because I had arranged to go along to the local tennis club that evening. Dadda was having his afternoon cup of tea, prepared by the long-practised hand of the girl – a woman now, getting into her late twenties as serenely as if they were already the lonely old age that lay ahead of her – who had been his first employee. I stayed to have one with him. I mentioned Anna’s new preoccupation:

‘It’s the sort of thing that’s all right for silly old women – and Henry, of course – but I’m surprised at Anna going in for it.’

Dadda sucked at his tea thirstily. ‘There could be many worse things than that, I think.’

‘You’re not going to defend it – all that mumbo-jumbo?’

‘Only for Anna. She is clever and lonely, and the world can be hard. For the young especially.’

I glanced at him. He sat hunched up in his chair; he had a look of concentration, almost of pain.

I said: ‘It’s lucky I’m not clever.’

‘You are not lonely. You have a softness, and with that you are not lonely. The lonely are the hard ones. The world is hard, and the soft ones are bruised by it, but the bruises heal. The hard ones, the lonely ones, are chipped and broken.’