‘There is only me now’

‘And your sister Angela?’

‘She got married during the war. They have three children.’

‘I remember her as the most beautiful person I have ever known.’

‘She has a daughter,’ Hibson said, ‘very like her. What about your people? Your father?’

She looked up at him, her brow still furrowed. ‘They are dead. There is only me now.’

‘But your brothers?’

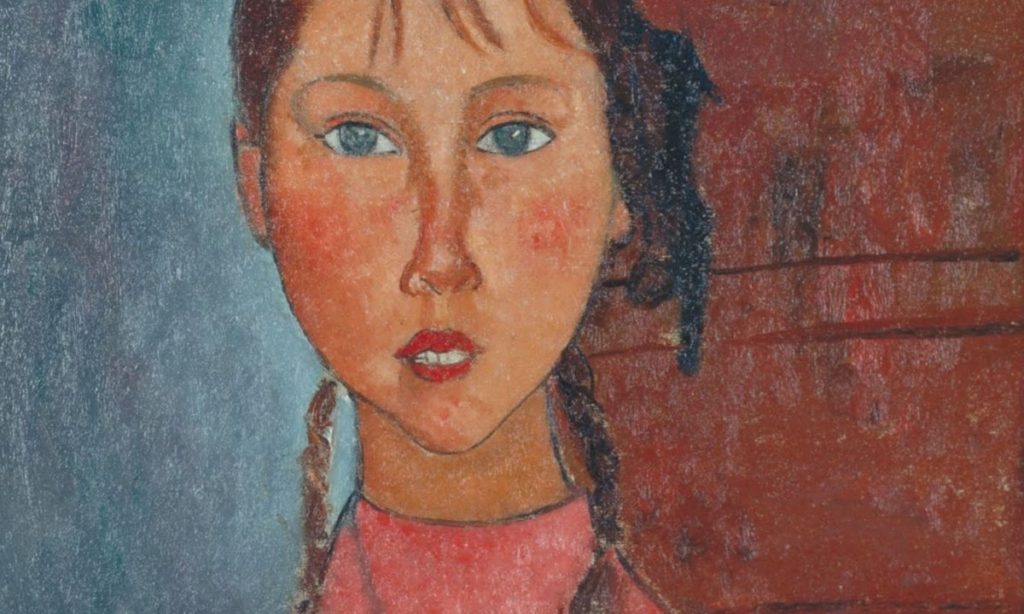

There was only Irina, then, the little girl in pigtails – she could not have been more than eight at the time. It would not have been mentioned before her. She would not have known anything.

He said: ‘I’m sorry. What happened?’

‘It was in the war.’

‘But weren’t you all here, in Switzerland?’

Her eyes evaded his and he recognised, with surprise, that there had perhaps been more to fear in the encounter for her than for him – that, for her, pain was something which still suffused the heart and being, not an old scar that, protected, gave no trouble. At this moment the deaths of her father and her brothers meant nothing to him but a sense of relief, but he was moved by her grief over them. He said quietly: ‘I’m sorry.’