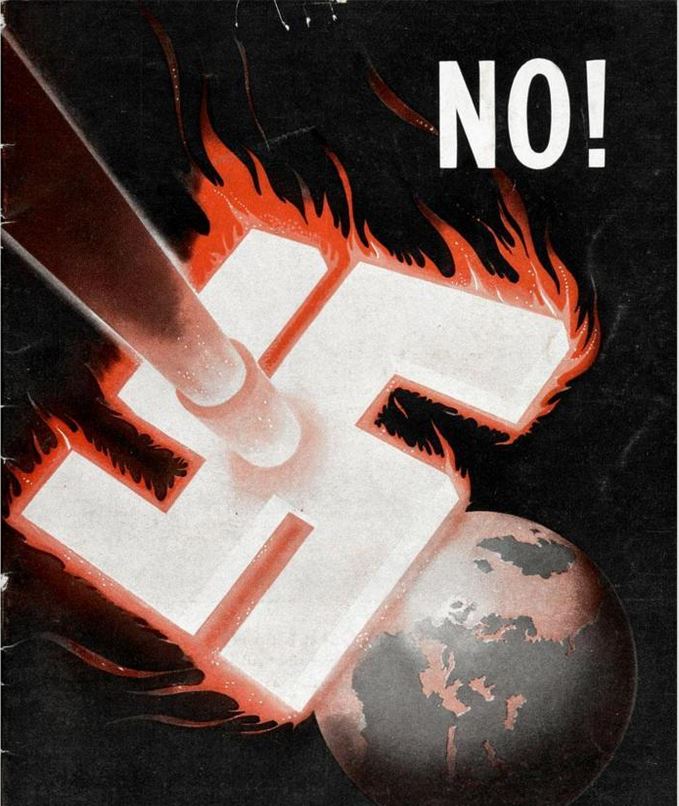

To England and Germany and peace

The food had been eaten, and there were cries for a speech from the groom. Isaak, when it had been made clear to him what was required, stood up. He looked around the mass of strange faces, and smiled easily.

The food had been eaten, and there were cries for a speech from the groom. Isaak, when it had been made clear to him what was required, stood up. He looked around the mass of strange faces, and smiled easily.

‘My friends,’ he said. ‘You are all my friends because you are the friends of my wife. I am a thief, my friends. The police should take me. I come to your country and I steal – I steal your Jinny from you. Now she is my Jinny, and she is a German.’ He hesitated for a moment. ‘We have fought a war, your country and mine. It must not happen again that two such great countries should spill each other’s blood. It will not happen again. Jinny and I will not let it happen.’

He spoke with an assurance and gaiety that impressed me deeply. For many years to come I would think of Isaak when some mention was made of German political intentions, and wonder, half-credulously, what Uncle Isaak would do about this.

‘Let us drink a toast,’ Isaak said. ‘To England and Germany and peace.’

I drank the toast in the remains of my watered claret cup. Long, long afterwards, in the Western Desert, a handful of us drank to the indecent doom of the German eagle with looted Italian wine, and I saw Isaak’s face against the chill night sky of Libya.