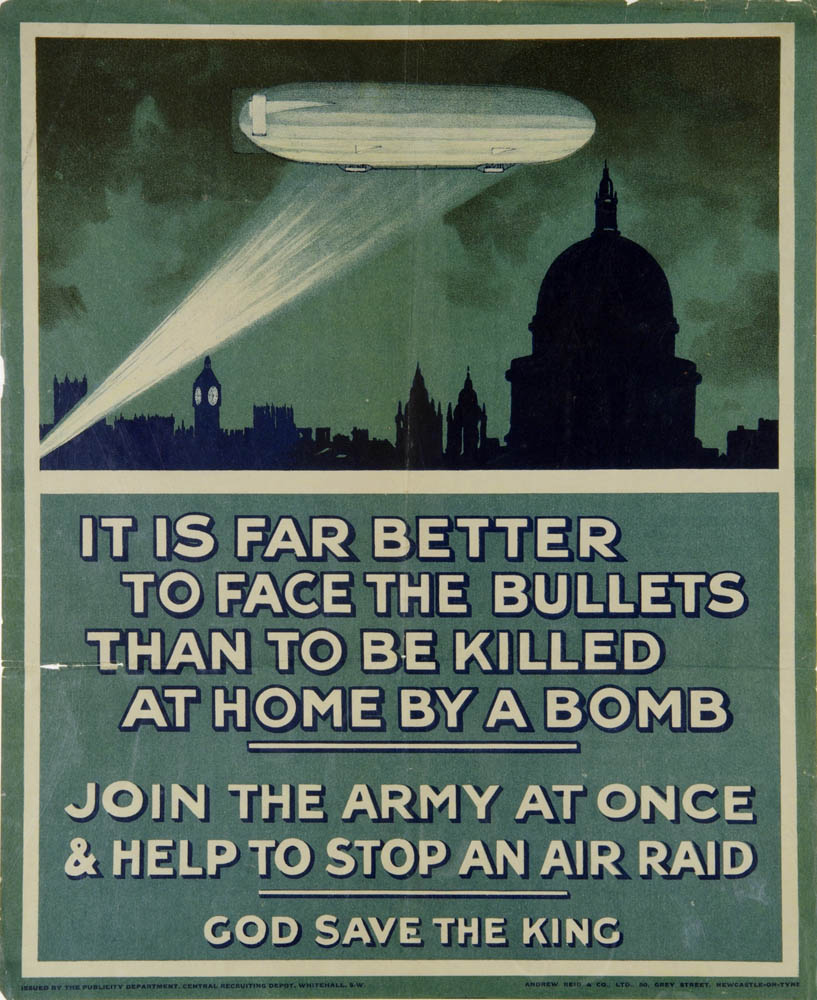

Leaving an earthly paradise

There was the usual little ceremony at the office when Lance left. Two other clerks ha d also received their papers, and one of the girls was leaving to join the A.T.S. Mr Bengear himself paid for the afternoon tea and cakes, and presided over their serving in the typists’ room. His small, fat paws stretched out as though to bless, and tiny drops ran down from his hair to settle in the grooved scar that ran across his forehead.

d also received their papers, and one of the girls was leaving to join the A.T.S. Mr Bengear himself paid for the afternoon tea and cakes, and presided over their serving in the typists’ room. His small, fat paws stretched out as though to bless, and tiny drops ran down from his hair to settle in the grooved scar that ran across his forehead.

He said: ‘Well, young men, you’ve got to go. You must exchange your clothes for uniform, your sheets for Army blankets, your five and a half days a week at the office for seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day, in the Army. I don’t know how you are feeling about it now, but I can assure you that within a month you will be looking back on your life here as a snatch of earthly paradise.’

The typists giggled. Mr Bengear quelled them with a pudgy wave.

‘Despite my fat,’ he went on, ‘I have a vicious nature. In 1916 in the trenches, and even more in the arid desolation of Base Depot when I had at last managed to wangle a job there, I thought of this happy future. I thought of how I should wave good-bye to the next generation as they went forth into slavery. Such thoughts. Such happy fulfilment!’

His round, merry face clouded.

‘Though, after all,’ he said, ‘perhaps you will like the Forces. Perhaps I am unusual in that respect. Certainly, although I met few who liked the life while I and they were in it, all I meet now speak of the old days with a certain, sentimental regret.’

Mr Bengear lifted his cup and drank the steaming tea.

‘Anyway,’ he finished, ‘we shall miss you. I shall miss you even while I gloat. And I beg you not to take the gloating too much to heart. Set your minds instead on the next war when you will be waving good-bye to the youngsters yourself, and old Bengear will, very probably, have passed beyond.’