Ready for your nightcap?

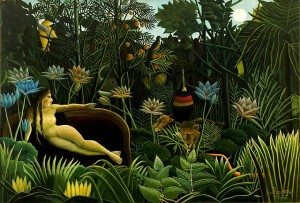

Over supper she made a lot of jokes which she knew at the time were pointless, and drank a good deal of palm wine. At the same time she was aware of a different tension rising inside her. Her hands clenched, unclenched and clenched again. In the end it reached such a pitch that she got up quickly and left the others. She walked back to her hut, a little drunk and detached, conscious of the separateness of her body, and of its restlessness.

Billy, as always, had lit the two night-lights in her hut. They were made after a pattern the Hawaiians had shown them in the early days: there was a plant which, when pressed, gave an inflammable vegetable oil, and another, the thick flax-like fibres of whose leaves could be used as wicks. They burned with a dim oily light, one by her bed, the other near the door.

In the past the light by the door had been her signal for privacy: she put it out before she undressed, and that meant she was not to be disturbed. If it was still burning, Billy would bring her a drink of fruit juice before he turned in himself. He would serve it in as stewardly a fashion as possible, considering his tattered clothing and unshaven face, and sometimes she would have him talk to her for a while before dismissing him. She thought about this for what seemed a long time; the voices of the others came thinly across the clearing, and something, probably a monkey, was howling out in the forest. She picked up the light from beside the bed and took it over to rest beside the other. Then, moving back into the shadows, she stripped the clothes from her body.

She lay on the bed, perfectly still, waiting. She heard Billy’s footsteps as he approached, and his voice at the door:

‘Ready for your nightcap, miss?’

‘Yes,’ she said. Her throat was dry. ‘I’m ready.’