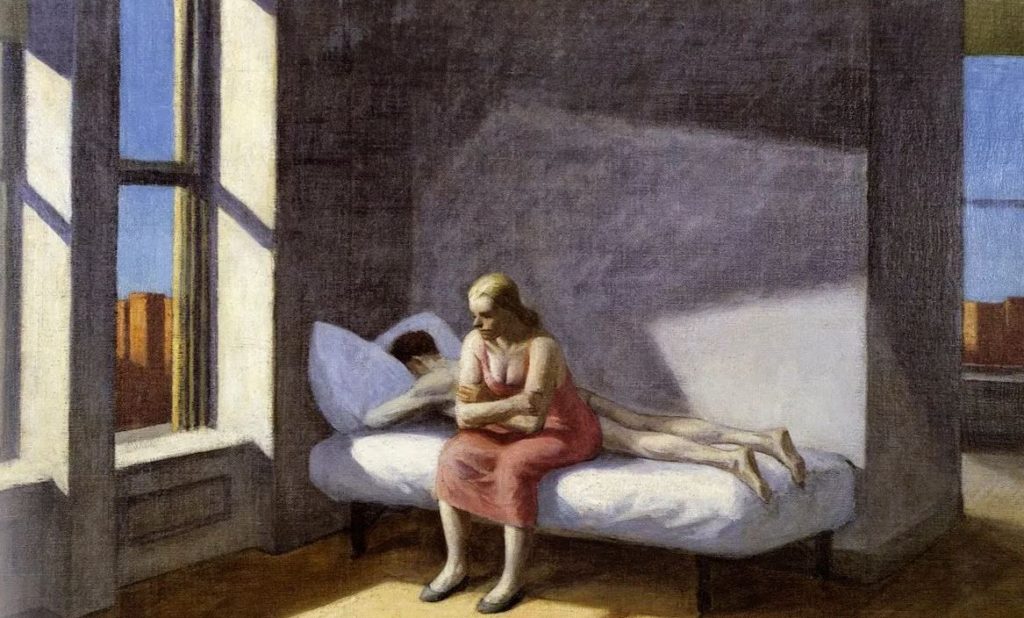

The poor bones of self and circumstance

Andrew went to sleep quite soon. When he awoke there was light from a half moon, just lifting clear of the branches of the trees. Madeleine seemed to be peacefully asleep. He got up quietly, so as not to disturb her, and walked up into the grove. It was somehow lonelier there than on the long deserted beach. He stretched himself; his back and shoulders were stiff and cramped.

He went back to the beach, but to the other side of the dune. Although the night was still warm, he found himself shivering. He was conscious, in this penetrating shadowless brightness, of all that he had lost. His job, and England itself, seemed unreal when he thought of them. For the boys, who, he now saw, would inevitably drift from him into whatever chequered difficult lives lay before them, he felt a mild regret. For Carol, none; not even disgust. In this night’s limpidity, the things which had belonged to him – which he had thought important – lost all meaning. He had no longing for them.

What he felt was not, he knew, a sense of loss. It was worse than that: a sense of nakedness, of being stripped down to the poor bones of self and circumstance. The things that had gone had been illusions, but he did not see how he would survive without them. The pain he felt was worse than the pain of love; because in love, always, some hope lingers.