His first break from work

Solly looked round the office. ‘You have done well here, Benno.’

‘I have survived.’

‘I meant that. The worst is over now?’

Dadda nodded. ‘I think so. It has been bad, and now it is a little better.’ He smiled again. ‘I think it will not hurt to leave things for the rest of the day. We should go and have a drink together, since I too am an uncle now.’

Like many men professing atheism, Dadda placed much reliance in the workings of what he would have called, but for the general restraint of his emotions, Fate. He saw its presence very clearly in the events of this morning – some great finger arrowing down to alight, miraculously almost, on him. So many things happened together – the news from Germany, Solly calling in at the office instead of the house, his own decision to take his first break from work in over three months – that he could not believe them to be fortuitous. His saving grace was that he looked for his destiny in fortunate strokes; when the blow was against him he was too concerned with combating it to ponder its origin.

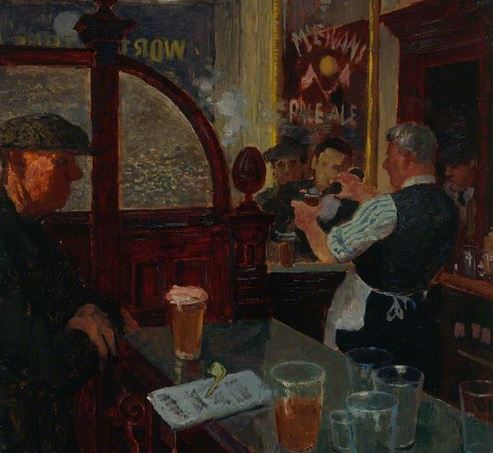

During all his time at the office, Dadda had never yet been into a public-house in that district, and it was Solly who suggested The Grapes, a solid late-Victorian establishment whose great expanses of mirrors gleamed with the light of glistening brass.

‘I used to come here sometimes, before the war,’ Solly said. ‘The landlord was Joe Veinitch; he died and his widow sold up. I don’t know who has it now.’

Dadda said: ‘What will you drink, Solly?’

It was only just turned noon and the long bar was almost empty. Above the bar counter were fixed rows of casks – Sherry in the Wood, Port in the Wood, Rum in the Cask – and below them there were arrays of bottles.

‘I always drank mild ale,’ Solly said. ‘I’ll have that now. A half.’

Dadda put down sixpence, and pocketed the penny change. The glasses were set in front of them, headed with a fine rim of froth.

‘To Patrick Rosenbaum,’ Dadda said. ‘And to the happy parents.’