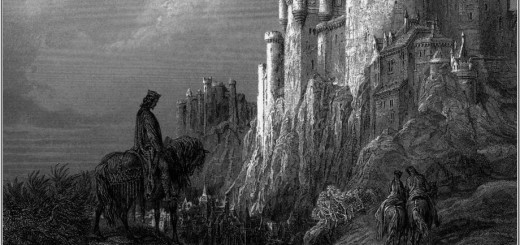

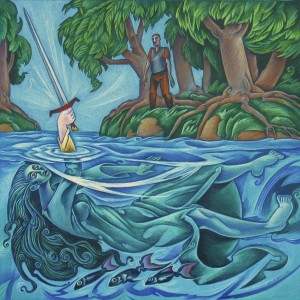

The lady of the lake

‘The ruins of the castle further along the lake are twelfth century, but these are said to be the remains of an earlier structure. Roman, maybe.’

‘Or the castle in which the Lady of the Lake lived – the one who gave Arthur Excalibur.’

‘You’ve heard that story, then?’

‘Sir Donald told me. And about Carmaliot being Camelot.’

‘The countryside is full of such tales, but it surprises me any sensible person takes them seriously. The lake is said to be bottomless, too. When we were children, Andrew and I took out a boat and plumbed it, with a weight on the end of a rope. The furthest depth we found was not much more than seven feet!’

‘Which of you proposed the measuring?’

She shrugged. ‘I don’t remember.’

‘I will guess it was you. You are too practical altogether.’

‘One needs to be in Cornwall, in self-defence. If not, one might find oneself believing all sorts of things: witchcraft, and owls and ravens being evil spirits, and hares being ghosts of the dead. The tinners used to frighten themselves with tales of knackers.’

‘Knackers?’

‘They were supposed to be gnomes who lived underground. They looked like little old wrinkled men, but they were also said to be able to change their shapes, and to vanish into smoke. Consistency is not the chief quality of country tales. They were held to be very evil and malicious, too, and since the mine workings were their favoured haunts, tinners were reluctant to go below unaccompanied.’

I thought of underground rocky galleries, pitch black except for the light of the miner’s lamp, and shivered.

‘I can imagine that.’

Emily poured us tea. She said:

‘Anyway, the Lady of the Lake did not have a castle – she lived under the lake.’

The shiver had passed. The day was warm and bright, and Emily was putting milk in my tea. The lake stretched blue and calm beside us. I felt lazily content. I said:

‘How could she – live under the lake, I mean?’

Emily passed me my cup.

‘I have a notion you are the kind of romantic who expects romance to be governed by reason. How very unreasonable of you.’