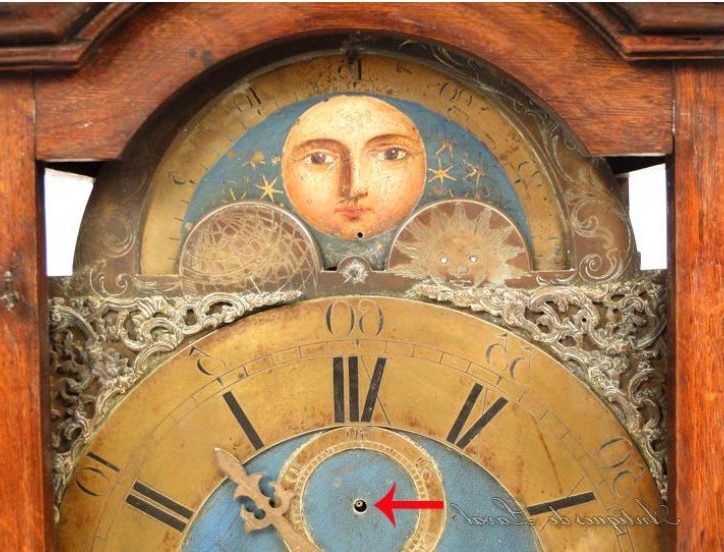

Winding the clock

I had warned Miss Wistreich that we should be coming; and she appeared at the top of the steps as the cars drew up at the front door. She usually kept one of the children with her on such occasions to abate her nervousness; to-day she had two. Her head jerked involuntarily on her frail neck as I introduced them all. She hid her face, as soon as she decently could, in turning to the children.

‘And these are Janet and Cynthia,’ she said brightly. ‘Say hello to Mr. Glebe and his friends.’

Janet was a spindly, fair-haired child with a leg-iron. The metal flashed like silver in the sunshine as she bent her good knee in a curtsey. The other girl was smaller, with dumpy features and nondescript hair and only one hand. Our Cynthia bent down to her, her well-groomed head almost touching the untidy freshness of the child’s.

‘Hello,’ she said. ‘My name’s Cynthia, too.’

In the Library Miss Wistreich poured out sherry for us; she had let the children go and her head was shaking more noticeably. Holding a glass uncertainly herself she said with determined light-heartedness:

‘You mustn’t forget the clock, Mr. Glebe!’

Lulu said: ‘The clock? What clock?’

Miss Wistreich smiled twitchily. ‘Mr. Glebe winds it up – it’s a thirteen-month clock. It’s in the hall, as you come in.’

I said: ‘We’ll see to it now. No, stay and finish your drinks, the rest of you.’