A good run!

He set Bucephalus to a gate, and felt the response of the horse with a delight that no response of woman had ever given him.

Michael came up on his right, and with the excitement of a boy, he called:

‘A good run!’

Michael shouted back: ‘A good day!’

He smiled at the smiling face of his son, realising in the renewed companionship of shared exultation the artificiality of the guilt he had felt over the land sold, the birthright narrowed down. He understood at last how Michael accepted things; simply, with no need for explanations and recriminations. Life was there to be taken at its best; enjoyed like a woman, or a book, or a good wine. Argument only rendered it sterile.

He glanced round briefly. The field was strung out over more than half a mile. They were up with the leaders; Michael a couple of lengths away on his right and the withdrawn and imperturbable Rosemary just beyond. At a whim he thought: I’d like those two to marry. That calm, that assurance! Even if it’s only coloured bubbles I’d like it in the family.

Up the spur of the hill, through a patch of timber, and the valley stretched before them, dim and darkening. Beyond the milling torrent of the hounds he saw a flash of brown, moving more slowly as her strange and unjust destiny yelped and barked and thudded and shouted at her heels. What have we to do with justice, he thought, answering her mute accusation with the humble pride of a god. We only live, we do not question or purpose.

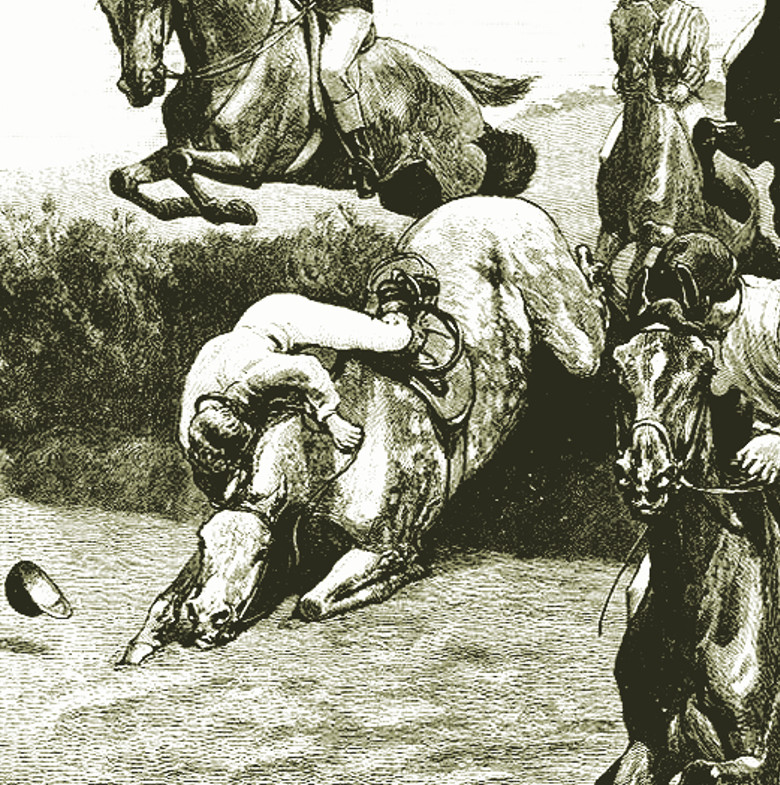

Sympathetic as he was to each slight motion of the horse beneath him, he knew at once what had happened when Bucephalus began to crumple forward, dreadfully swift and yet perceptible, as though a ship were foundering. His right foreleg in a pot-hole – and a deep one, his mind added, as the collapse accelerated. He felt himself falling free and his head hit the ground and pain fastened on him out of the shadowy sky.

Someone was helping him up, out of the way of a horse that kicked in agony beside him. A man said:

‘Are you all right, Father?’

He moved his head, but the pain lanced down into his neck.

He said: ‘Yes. I think so. Thanks.’

It was like thinking in a fog. Something had happened. A fall. He looked at the horse, and looked away. He tried to remember the horse’s name. If he could remember that, he felt, the fog would lift. But he could not remember, and the fog thickened.

It shivered as the sombre note of the mort floated over the hillside, but it did not lift.